In its calls for projects in the Horizon 2020 programme, the European Commission challenged the consortia to develop a strategy for the projects to obtain and maintain a ‘Social License to Operate’ (SLO). In this conference call, the SLO-approach by the SecREEts project is presented and compared to the model proposed by Boutilier and Thomson (2011).

This conference call is part of a series of meetings of the high-level multi-stakeholder expert panel in search of the development of a series of policy recommendations for the EC. The next meeting is scheduled on November 22, 2019 in Brussels.

Introduction

The EU H2020 projects NEMO, CROCODILE and TARANTULA aim to enhance resource recovery from primary and secondary streams. All three projects combine these technological innovations with a strong stakeholder involvement. They propose an enhanced dialogue framework between industry, government, academia and civil society in order to obtain and maintain the ‘Social License to Operate’ (SLO). They combine of a ‘bottom-up’ approach, where case studies are followed closely, with a ‘top-down’ high level multi-stakeholder expert panel which analyses trends, discusses lessons learned and develops policy recommendations on the issue of SLO and public acceptance. This conference call is part of this ‘top down’ strategy.

The SLO approach in the SecREEts project

(cf. powerpoint presentation and working paper)

The main objective of the SecREEts project (‘Secure European Critical Rare Earth Elements’) is to support a competitive and environmentally friendly European value chain for rare earth elements (REEs), based on the phosphate-rich stone used in fertilizer production. The project focuses on Praseodymium, Neodymium and Dysprosium used in permanent magnets for electromobility or offshore wind turbines.

SecREEts brings together a consortium of complementary industrial partners led by SINTEF. Next to driving the technological innovative research, SecREEts assesses the social, environmental and economic sustainability of the value-chain. The Prospex Institute is responsible to assess the social sustainability of the process and to push for a transparent and trustful relationships with all relevant actors.

In the SecREEts project, a thorough stakeholder mapping was done via the CQI-method, where a series of Criteria are defined, Quota per criteria or category are set, and Individuals are identified[1]. This method was applied on two locals cases, namely Ellesmere Port (UK) and Porsgrunn (NO) where local “Citizens Labs” were organized. In both cases, they found the local stakeholders very interested in the SecREEts project, its activities and the global context of REEs. Transparent knowledge exchange from the beginning and the clarifications of expectations were instrumental to a positive relation.

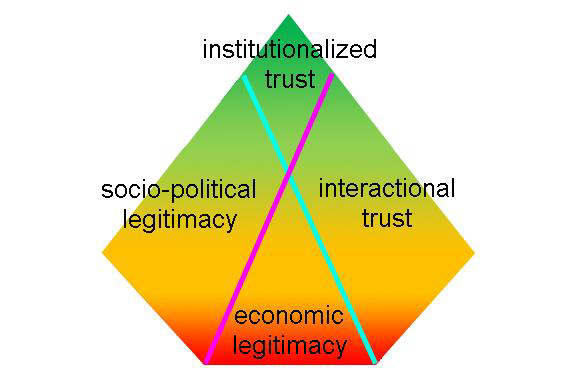

Boutilier and Thomson (2011) define a SLO as “… a community’s perceptions of the acceptability of a company and its local operations.” They identify four levels of SLO, going from withholding or withdrawing to acceptance, approval and finally psychological identification. Legitimacy, credibility and trust are key boundaries that influence the level of SLO. Further, they define four factors in an arrowhead model, which determine the level of SLO (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Levels of Social License with the Four Factors that Determine the Proportions of Stakeholders at Each Level (Boutilier & Thomson, 2011)

This SLO approach was compared with the activities of the SecREEts project. In the case of SecREEts, the defining factors were described as follows:

- Economic legitimacy: understanding longer-term opportunity of the project (economic credibility).

- Socio-political legitimacy: Positive contribution to local way of life.

- Interactional trust: the relation with local stakeholders knew good initial start, but will be defined by the results of follow-up actions on stakeholders’ suggestions and activities.

- Institutionalized trust: difficult to assess as the researchers are intermediary facilitators, and only have a limited time frame (duration of the project).

In general, the model of Boutilier and Thomson seems to apply quite well on the two cases, but achieving an ‘SLO’ remains a work in progress and many questions remain with respect to interactional and institutionalized trust.

After the presentation, several questions and comments were given:

- The historic experiences with industrial activities (e.g. mining) often influences the perception of new activities. Also, the educational level might play a role in the understanding of the discussed processes of the activity.

- The definition of SLO by Boutilier and Thomson (2011) seems rather passive, while their arrowhead model implies a (pro)active approach.

- The nature of a mining project versus a recycling or a research and innovation project is very different, despite that they might pursue the similar objectives (providing raw materials). Circular economy and urban mining might present a strong opportunity to engage more closely with civil society and the public at large. This might become the main focus of a follow-up mineral resource governance report, promoted by the UNEP – IRP.

- A strong institutionalised trust needs to be constructed progressively via a long term relationship. It starts from personal relation with key contact persons; later on, these persons can help to reach more people (snowball effect).

- Raising public awareness is a strong tool for SLO. Sharing information and knowledge about a process is often a sensitive issue for industrial partners (cf. Intellectual Property Rights issues), but key in gaining trust.

- It is important to consider local stakeholders as active partners in the production and exchange of information and knowledge. It is a two way process to which local stakeholders can contribute. This exchange can strengthen trust, induce co-learning and support a stronger involvement of more partners.

- The presented case allows to analyse how a project, as an intermediary body, can support or contribute to the SLO relationship between a company and its local stakeholders.

Next steps

The next meeting of the high-level multi-stakeholder expert panel is scheduled as a satellite event on November 22, 2019, during the EU Raw Materials Week in Brussels. A broad cluster of projects will invite speakers from industry, governments, NGOs, local citizens, academia and international institutions to present and debate their perspective on SLO and request each speaker to propose one key policy recommendations with respect to the public acceptance of mining and recycling. During the debate the alignment of these recommendations will be discussed.

References

Boutilier, R. G. and I. Thomson (2011). Modelling and measuring the SLO. Invited paper presented at seminar entitled, “The Social License to Operate” at the Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

Gramberger, M., Zellmer, K., Kok K., and Metzger, M. J. (2014). Stakeholder integrated research (STIR): a new approach tested in climate change adaptation research. Climatic Change 128(3) 201-214.

Download here the powerpoint presentation and the working paper.

Acknowledgements

|

The NEMO, CROCODILE and TARANTULA projects have received funding from the European Union’s EU Framework Programme for Research and Innovation Horizon 2020 under Grant Agreement No 776846 (NEMO – https://h2020-nemo.eu/), GA No 776473 (CROCODILE – https://h2020-crocodile.eu/) and GA No 821159 (TARANTULA – https://h2020-tarantula.eu/). |

With special thanks to Martin Watson and Clara Boissenin (Prospect Institute) of the SecREEts project (also EU H2020 funded under Grant Agreement No 776559).

Previous activities

On June 6, 2019, the NEMO, CROCODILE and TARANTULA projects joined efforts with the MIREU project to organise a workshop on “The way forward for ‘Social License to Operate’ (SLO) in Europe”. An article summarizing the main lessons learned was published on the KU Leuven SIM² website (Read more: kuleuven.sim2.be/ensuring-the-slo-concept-is-adaptive-and-resilient/).

On July 8, 2019, the UN International Resource Panel was invited to present its recently launched a report on ‘Mineral Resources Governance in the 21st Century – Gearing Extractive Industries Towards Sustainable Development’. During a short webinar the international framework was presented and a.o. the concept of ‘Sustainable Development License to Operate’ (SDLO) was introduced. (Read more: https://kuleuven.sim2.be/gearing-extractive-industries-towards-sustainable-development-webinar-report/)

[1] See Marc Gramberger, Katharina Zellmer, Kasper Kok & Marc J. Metzger, 2014: Stakeholder integrated research (STIR): a new approach tested in climate change adaptation research. Climatic Change 128(3) 201-214.