Cement is the most used building material in Earth. Its production and consumption are very well stablished across the countries. Can you think of a reason to change that? What if that high demand for cement could be also met if we were able to use cement wisely, giving the stage to less CO2 intensive materials? At this point, you might have asked yourself: but why would we want to replace a material that we know so well? Unfortunately, cement, an apparently ordinary and harmless material, hides a somewhat dark side.

My name is Natália, I am ESR13 of SULTAN Project, working in Zurich, Switzerland. The research that I carry out in SULTAN is greatly motivated by the provision of adequate disposal for mine wastes. I want to reach it by producing a type of concrete that encapsulates the tailings and prevent them from doing harm. To do so, I need to understand the role of cement on this tailings-based concrete. But my interest in cement dates from 2011, when I started my studies in civil engineering. Since then, when I first learnt about cement and its importance, I have been driven by my interest in construction materials and sustainable construction. Maybe that is the reason why I have decided to write my first blog post about cement. So, here it starts. Enjoy the reading!

Cement is the most used building material in Earth. Its production and consumption are very well stablished across the countries. Can you think of a reason to change that?

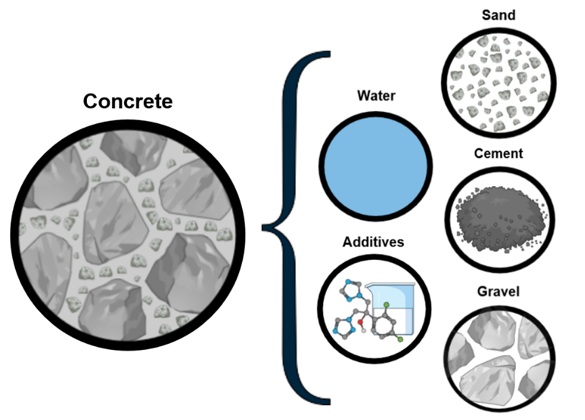

Cement is a typically grey, reactive powder that is used to produce concrete. There are several possible recipes to produce concrete, but nearly all of them include the following ingredients: cement, sand, gravel, water and additives. When they are mixed, they form a bulk which solidifies over time, as the chemical reactions between cement, water and additives progress. Additives are materials that can be included in the mix to improve specific properties of concrete, either in its fresh or hardened state. So, for now, we all know that cement and concrete are not the same, correct? However, cement is the most important ingredient of the concrete mix. It is the material responsible for binding the other ingredients and, as a consequence, for creating this unique artificial ‘rock’, which we call concrete.

Figure 1. Ingredients of the concrete mix.

The properties of cement products, such as concrete, have been extensively researched. Due to this, cement is a widely known, accepted and reliable building material. Despite its omnipresence at construction sites all over the world, something we might not be aware of in our everyday lives is that cement and concrete are actually highly important for the planet’s sustainable development. This is because concrete is the main construction material used for building the infrastructure required by the growing economy and population. Economic development and urbanization directly relate to construction of infrastructure and housing, which in turn consumes extremely large amounts of cement. To give a picture, more than 4,000 million tons of cement are produced annually, most of them by China, India and the U.S. [1].

Buildings and infrastructure are not the only application for cement. In mining, for instance, cement has been used as a binder agent in cemented backfill technologies for underground mines. (I confess that I have special interest in that application, since it is the subject of my PhD research in SULTAN JBut let’s keep the focus on cement…). Thus, cement production needs to run at its highest power to be able to meet the demand.

What if that high demand for cement could be also met if we were able to use cement wisely, giving the stage to less CO2intensive materials? At this point, you might have asked yourself: but why would we want to replace a material that we know so well? Unfortunately, cement, an apparently ordinary and harmless material, hides a somewhat dark side.

Over the last 60 years, the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere has had a 30% increase, mainly due to the emission of fossil fuels, deforestation and cement production [2]. And it kept rising on the past few years, after achieving some stability between 2014 and 2016 [3]. That means that cement production is responsible for a considerable portion of the CO2emitted by human activities – around 5-8% of the global total, according to estimations [1][4]. Maybe 8% does not seem to be a high number, so I can put it in other words: if the cement industry was a country, it would be third in the ranking of CO2emissions per nations, behind the United States and China, and ahead of nations such as India and Brazil.

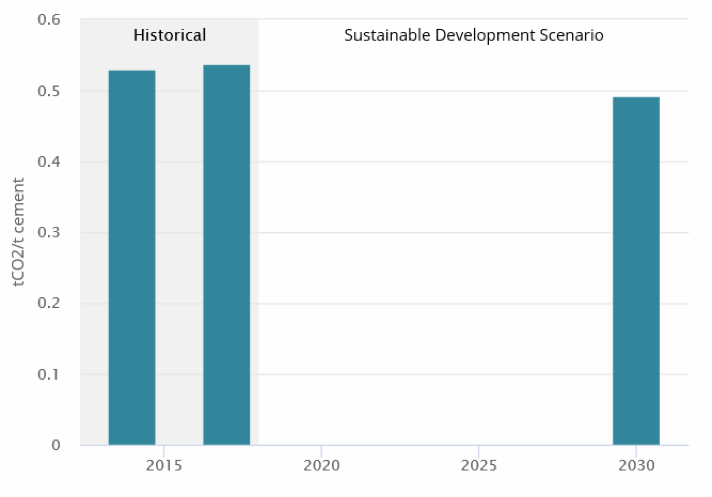

The greatest amount of CO2is emitted in the production of clinker, the main component of cement. Other contributions come from fossil fuels that are burnt in the kilns, from grinding and from transport of raw materials. The industry has tried to improve energy efficiency and has implemented changes in the production process in order to account for the demands of sustainable development. The use of alternative fuels and the reduction of clinker content in cement are examples of changes that have been done. As a result, the specific emissions of cement i.e. kg of CO2per kg of cement, are reducing, especially when compared to other conventional building materials, such as glass and steel [4]. However, much more effort is needed in order to make a real difference in predicted scenarios [5].

Figure 2. Energy-related and process emissions of cement [5].

Even though the specific emissions of cement are not the highest among building materials, the overall numbers are a warning: we use too much cement. The large amount of concrete used annually by human kind is what makes the overall cement-related CO2emissions so high. And that scenario will not change until we change the way we build.

That is the main reason behind the idea of encouraging the use of less CO2intensive materials to replace cement products in its several applications. Those can include bio-based materials, natural pozzolans, industrial wastes, earth from excavation and several others. The use of locally available green materials leads to additional reduction of CO2emissions from transport.

We can also learn from ancient civilizations. Much before the advent of cement as we know it, the Romans were able to produce durable concrete using environmental-friendly materials that dismiss CO2intensive industrial processes such as the one used to produce cement. And, amazingly, Roman concrete remains durable after 2000 years! Even structures that were built under seawater endured in such an aggressive environment [6]. So among many things that the Romans taught us, they have shown us that it is possible to build durable structures in a different way, using materials other than cement.

In 2018, I experienced sustainable construction for the first time, on a project called CIAC. The project involves designing and building a community center in a big Brazilian city called Fortaleza. After its construction, the CIAC Project will offer social support and education to children who live in the community. The team ahead of the project decided to make sustainability a rule. The center is being built using earth as the main construction material, and the community is able to actively participate in the construction process and learn about the techniques used. We have used different techniques to build with earth and explored some of the amazing properties of this building material. I would like to finish this article with some pictures taken during the construction that confirmed a very important lesson to me: we can change the way we build!

.png)

Figure 3. Preparation of the mixture for taipa construction (Photo by Andre Souza, 2019).

.png)

Figure 4. Taipa construction of internal walls (Photo by Andre Souza, 2019).

.png)

Figure 5. Hiperadobe (Photo by Andre Souza, 2019).

.png)

Figure 6. External wall made of hiperadobe (Photo by Andre Souza, 2019).

.png)

Figure 7. Top-view of the construction site (Photo by Andre Souza, 2019).

.png)

Figure 8. Adobe blocks (Photo by Andre Souza, 2019).

Thank you for reading!

I would like to invite you to go through the articles below if you are interested in reading more about the topic of this post.

[1] J. Timperley (2018) “Q&A: Why cement emissions matter for climate change” < https://www.carbonbrief.org/qa-why-cement-emissions-matter-for-climate-change> (accessed July 28, 2019).

[2] T. Radford (2019) “Human carbon emissions to rise in 2019.” <https://climatenewsnetwork.net/human-carbon-emissions-to-rise-in-2019/> (accessed May 24, 2019).

[3] M. McGrath (2018) “Climate change: CO2 emissions rising for first time in four years.” <https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-46347453> (accessed May 24, 2019).

[4] L. Barcelo, J. Kline, G. Walenta, E. Gartner (2014) Cement and carbon emissions. Materials and Structures, V. 47, n. 6, pp. 1055–1065. https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-013-0114-5

[5] The International Energy Agency (2019) “Cement. Tracking clean energy process”

[6] S. Yang (2013) “To improve today’s concrete, do as the Romans did.” <https://news.berkeley.edu/2013/06/04/roman-concrete/> (accessed July 28, 2019).